Teachers who know they can choose how they teach are able to empower their students to learn.

3C Learning and Teaching

Showing posts with label LEARNERS. Show all posts

Showing posts with label LEARNERS. Show all posts

Friday, February 12, 2016

Learning Strategies

Learning is such an individual experience! We all have our own way to learn, and the orientations, approaches and strategies we use for learning have been acquired during childhood and educational experiences, thus becoming quite stable by constant reinforcement and tending to last throughout our lives. However, it is possible to help students to become better learners by teaching learning strategies and metacognitive skills as byproducts of the subject matter.

We live in a world where life-long learning is a must. It doesn't have to be formal, academic learning, but being able to adapt to the new technology and the rapid changes in our lives. Where ever I teach, I always want to support my students' self-regulated learning by engaging in process-oriented instruction and learning facilitation (as seen in Simons,1997).

Sometimes people confuse learning strategies with instructional strategies, but these are two distinctively different concepts. Instructional strategies are used by the teacher, learning strategies are in each students' own repertoire. Sometimes also learning styles are confused with learning strategies. Distance Learning Association has a good online presentation about learning styles and strategies.

Vermunt and Vermetten (2004) concluded that students' learning strategy patterns generally belong to one of the following dimensions: undirected, reproduction-directed, meaning-directed, or application-directed. TheKalaca & Gulpinar (2011) table below displays the learning components attached to each learning strategy (called learning style in the table).

Learning often gets hard for students who rely solely on undirected or reproduction-directed learning strategies. Both approaches focus strongly on memorizing the content without connecting the details to a hypernym (i.e.umbrella term). With external regulation of learning, these students aim to pass the exams, but find it hard to assess their own learning.

Meaning-directed students try to first understand the entities and then relate the details into these bigger concepts. Focusing on learning in the context, these self-regulating students try to connect the new information with their existing knowledge. They may be critical, as forming an opinion about the topic is important, and they may engage in independent search for additional material to better understand the concepts to be learned.

Application-directed students value learning about useful materials and topics, and they try to find practical applications for the content they learn. Being both externally- and self-regulating, these students reflect on their own experiences and relate their practical knowledge to the theoretical concepts to be learned.

Students in all four dimensions benefit from learning more about self-regulation and metacognitive strategies in order to become life-long learners, and able to choose from the information and misinformation that is available on every computer and handheld devise. The necessary instructional strategy for teachers - in addition to supporting learning process and teaching metacognitive strategies in various ways - is to learn how to ask non-googlable questions.

Kalaca S, Gulpinar M. A Turkish study of medical student learning styles. Educ Health [serial online] 2011 [cited 2016 Feb 12];24:459. Available from: http://www.educationforhealth.net/text.asp?2011/24/3/459/101429

Simons, P. R. J. (1997). From romanticism to practice in learning. Lifelong Learn. Europe 1:

8–15.

Vermunt, J. D., & Vermetten, Y. J. (2004). Patterns in student learning: Relationships

between learning strategies, conceptions of learning and learning orientations.

Educational Psychology Review, 16, 359–384 http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10648-

004-0005-y.

Sunday, September 13, 2015

Wonderings about learning and intelligence

It seems that intelligence - or the way how we understand intelligence - is very much context dependent. In formal education those students who are able to reproduce the learning material delivered to them are often considered to be intelligent. This ability is evidenced by various exams, multiple choice tests, and other evaluations. The need to do well in exams is ingrained into students thinking very early on, and often students develop their (academic) self-concepts according to the grades they receive. To me this way of knowing (rule-based, or instrumental, see Kegan 1982, 2000; Drago-Severson 2004) is just a beginning of becoming a learner.

When you are invited to play a game, you most likely will want to follow the rules, in order to gain something from playing - whether it is winning a price like getting your diploma, or something else we perceive having value, like being accepted by your peers and other people. This certainly is socially intelligent behaviour, but how much does it really relate to the cognitive part of intelligence: the physiological effectiveness of out neural system in storing and retrieving data from the brain and the ways of knowing? Or understanding our own values and being willing and able to negotiate with those who have conflicting views?

IQ testing is an attempt to measure operational intelligence. The component behind our cognitive skills (language/math skills, logical reasoning, spatial sense, etc) is called the general intelligence factor. While I do recall going through reading speed testing at school, I never got the impression that intelligence would have been overly emphasized during my schooling. The message was more along the lines that everyone can learn and that we should engage in dialogue to better understand each other.

So, what about the meaning-oriented learning, and the intelligence that is much harder to measure by standardized IQ test? My own thinking about intelligence and learning is growing along the lines of the adult development and life-long learning, and I think that reproductive learning orientation is not sufficient.

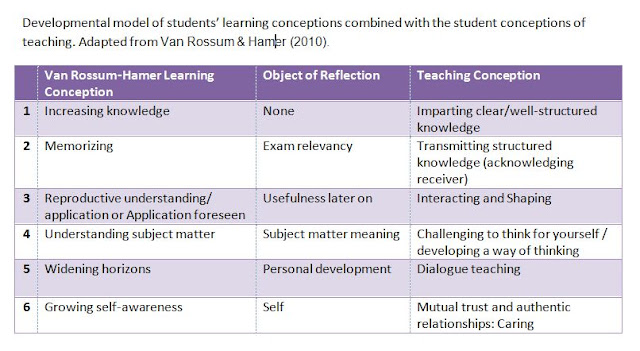

Van Rossum & Hamer have a fascinating book "The Meaning of Learning and Knowing" that has influenced my thinking about how we learn.

Learning as understanding the connections between different theories or models is the way I see broad/general intelligence to be used best. This type of learning includes challenges and problem solving, but also requires lots of collaborative meaning-making and learner agency being a central part of each individual journey.

I think I am a lifelong learner -- there is so much to lean, and so little time to do it!

wfe2

When you are invited to play a game, you most likely will want to follow the rules, in order to gain something from playing - whether it is winning a price like getting your diploma, or something else we perceive having value, like being accepted by your peers and other people. This certainly is socially intelligent behaviour, but how much does it really relate to the cognitive part of intelligence: the physiological effectiveness of out neural system in storing and retrieving data from the brain and the ways of knowing? Or understanding our own values and being willing and able to negotiate with those who have conflicting views?

IQ testing is an attempt to measure operational intelligence. The component behind our cognitive skills (language/math skills, logical reasoning, spatial sense, etc) is called the general intelligence factor. While I do recall going through reading speed testing at school, I never got the impression that intelligence would have been overly emphasized during my schooling. The message was more along the lines that everyone can learn and that we should engage in dialogue to better understand each other.

So, what about the meaning-oriented learning, and the intelligence that is much harder to measure by standardized IQ test? My own thinking about intelligence and learning is growing along the lines of the adult development and life-long learning, and I think that reproductive learning orientation is not sufficient.

Van Rossum & Hamer have a fascinating book "The Meaning of Learning and Knowing" that has influenced my thinking about how we learn.

Learning as understanding the connections between different theories or models is the way I see broad/general intelligence to be used best. This type of learning includes challenges and problem solving, but also requires lots of collaborative meaning-making and learner agency being a central part of each individual journey.

I think I am a lifelong learner -- there is so much to lean, and so little time to do it!

wfe2

Drago-Severson, E. (2004). Becoming adult learners: Principles and practices for effective development. Teachers College Press.

Kegan, R. (2009). What” form” transforms. A constructive-developmental approach to transformative learning. Teoksessa K. Illeris (toim.) Contemporary theories of learning: learning theorists in their own words. Abingdon: Routledge, 35-54.

Van Rossum, E. J., &

Hamer, R. N. (2010). The meaning of learning and knowing. Sense Publishers.

Wednesday, September 9, 2015

Children - natural born learners

Every child has a deep, innate curiosity about the surrounding world. This is the first learning environment we face. We all are born with a need to survive and experience the life, and to make sense of what we see, hear and feel. This is the force behind all real learning, and the reason for us to engage in the fundamental learning processes of acquisition and elaboration (Illeris, 2009).

We use the information we gather from out everyday lives to construct our understanding about ourselves, the life, universe and everything. Children are equipped with tools for learning to make sense of their surroundings - just think what all is accomplished during the first 2-3 years after birth! This informal learning is an enormous force the formal education has chosen not to use. Instead, children are pushed to engage in formal learning, which is much less enticing.

Not only are all children intelligent and gifted, but they are also motivated to learn - with their own preferences and developmenal curve. They are expert learners, because through purposeful play children experience the thrill of genuine achievement -- have you seen a child succeed for the first time in something they have repeatedly tried to do? Recall that triumphant smile? This is why we will want to support and nurture development in all broad learning domains:

We can nurture these skills in everyday exchanges and also in daycare, pre-school and kindergarten. But we cannot keep testing kids to formally evaluate what they know and can do, because the testing situation is not a natural envoronment for these super-learners. And we can learn to observe (and document, maybe with a photo) of how children are learning to know how to support their learning journey.

Here is a general list of definitions for good learners:

- Curiosity

- Pursuing understanding

- Recognizing that learning is not always fun (thinking of a two-year-old who wants to succeed, even if it is frustrating)

- Knowing failure is beneficial (this is the true Growth Mindset!)

- Making their own knowledge

- Always asking questions (multiple times!)

- Sharing what they have learned

Admittedly, this list was created for students in higher education. But I think good quality learning is universal and does not depend on the age of the learner. To reverse the negative effects of schooling we should teach about the growth mindset to empower deeper learning.

By the time children enter the formal education system they are already expert learners. Depending on the feedback children/students receive about their learning explorations, they will either continue to the direction they are headed, or venture into something else. Why don't we use their curiosity and enthusiasm by providing meaningful learning experiences and encouraging their questions?

Why do school systems choose to promote low level skills and compliance over critical thinking?

Illeris, K. (2009). A comprehensive understanding of human learning.Contemporary theories of learning, 7-20.

Thursday, September 3, 2015

Learning Cycles

When talking about

learning cycles we often refer to the processes that occur while we

perceive, choose, reflect, store and retrieve data and information that our surroundings provide. It

is often displayed as a cycle, because the new information needs to become a

part of the already existing knowledge in order for learning (i.e. acquisition

and elaboration, Illeris, 2009) to be meaningful for student. There must be

connections between the newly learned material and things we have already

learned. If the contradiction is too big students get confused and/or

disengaged. It is hard to be interested in something that doesn't make any

sense, which is the main reason for me to always emphasize the importance of

including choices for students in the basic design of instruction.

Instructional design aims

to improve the teaching and learning processes and occurs before the

actual teaching happens. Sometimes the design only focuses on individual

lessons, but even then it is fairly easy to include optional activities and

assignments for students, so that they can choose from a selection and find

something that is personally meaningful for them. In the teaching situation

we as teachers use different strategies, teaching methods and

techniques to enhance students progress in moving through these cycles of

perceiving, choosing, reflecting, storing and

retrieving. Some teaching methods emphasize reflection,

others emotional input or maybe learning from trial and error.

The cycle is still utilized either visibly or behind the scenes. My choice

most often is to talk about metacognition and make the cycle visible for

students, so that they have better grasp and control of their own learning

process.

There are different visuals available in the

internet about the learning cycle. Most quoted or modified is probably the

Kolb's (1984) experiential cycle, which has provided the prerequisites for my

own thinking about learning process.

No matter where is our preferred phase to start learning

(Experiencing, Reviewing, Concluding or Planning), there are certain things to

consider while we are setting the scene for learning, if we want the cycle to

be rolling and support the learning process:

- What is the role of the learner? Are they included in decisions about what and how they learn?

- Are learners' perspectives taken into account while planning the learning experience?

- Are individual differences accommodated and valued so that we won't have 26 identical "experiments"? (Please note: an experiment, like research, cannot have a known result before starting the experiment!)

- Are learners co-creators of the learning process?

These questions are not new. They are based on learner-centered principles of APA Work

Group in 1997. Designing instruction that supports learning is easier when we

use these principles of learner-centered education, and empower students to

engage in their own learning process.

Learning is extremely

individual, because what we each see/hear/think depends on our previous

experiences and the unique filters we all have. Thus, while presented with

the same information we process it in diverse ways. Even in a collective

learning situation we all are engaged in our own personal learning process.

Understanding that learning and teaching are not the two sides of the same coin

is the beginning. Students learn all the time, but they may not be

learning things we wanted them to learn.

To further explore the way

learning process is described within the experiential learning theory, you

might want to look into the Honey and Mumford (2000) learning style questionnaire based on Kolb's cycle.

Honey, P., & Mumford, A. (2000). The learning

styles helper's guide. Maidenhead, Berkshire : Peter

Honey.

Illeris, K. (2009). A comprehensive understanding of human

learning.Contemporary theories of learning, 7-20.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the

source of learning and development.

Kolb, D. A., Boyatzis, R. E., & Mainemelis, C.

(2001). Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new

directions. Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles, 1,

227-247

Friday, July 3, 2015

Learning and teaching philosophy

Every teacher has a teaching (and learning) philosophy they follow, either knowingly or being unaware of the beliefs that have an impact on the daily practice. I tried to trace back the steps to the most influential points in the development of my teaching philosophy.

It all began when I had to read Berger & Luckmann’s book

about social construction of reality for my M.Ed. studies in late 1990’s. It

was the hardest book I ever read – when I got to the end I couldn’t understand

what I had just read, so I reread it. And then again. But, that book taught me

how we actually do construct knowledge in everyday life situation (and while

studying, too, of course, but learning is NOT limited to the classroom). And as I don’t actually believe in

unlearning, I became very conscious of what my kids and students are exposed

to, and very, very curious to hear how they interpret what they see and hear.

Well, then there is the Hidden Curriculum (Broady, 1987). What a gem! What all lies behind our curricula? All our

traditions and practices and words carry a huge load of unnecessary items (i.e.

unnecessary or even harmful for learning) – and especially our words do that

(Bernstein, 1971) because they can so easily be used to wield unnecessary power

over others. And words can be interpreted in so very many ways! I should know,

as a non-native speaker I have sometimes weird connotations for words… not to

talk about pronouncing them weirdly!

I learned about the theories of Ziehe in nineties as well,

and in 2008 he talks about normal learning problems in youth. I am so very

opposed to the deficit-based educational model, because it labels and

categorizes students, and at worst makes them believe in these tags attached to

them. Schooling, or formal education, is just a continuation and specification

of already initiated “natural” learning process. Students should be empowered to become

life-long learners! This is why I think agency is such an important thing while

discussing or thinking about curriculum.

Students' agency is seen as students intentionally

influencing their own learning behaviours. Much of our self-regulation is based

on the positive learning outcomes during the early childhood experiences of

self-efficacy (Bandura 2006). Students’

agency, according to Bandura (2006, p.164-165) is a construct of four different

components: intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness and

self-reflectiveness. In the classroom these components apply straightforwardly

to students’ learning and academic performance. It really is a shame is a

curriculum is so prescripted that there is no room for students to learn how to

make good choices! This is also where my current work on my doctoral dissertation focuses: Students' perceptions of their learner agency. Very exciting!

Of course I have

assimilated and accommodated all wonderful theories from Bruner, Engestrom,

Ericson,, Illeris, Kegan, Kolb, Mahler, Mezirov, Piaget, Vygotsky, Wiggins and beyond… but my core

belief is in cognitive approach being combined with constructive and

cooperative practices to enable effective lifelong learning.

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human

agency. Perspectives on

psychological science, 1(2),

164-180.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. T.(1966). The

social construction of reality.

Bernstein, B. (1971). On the

classification and framing of educational knowledge. Knowledge and control, 3,

245-270.

Broady, D. (1987). Den dolda laroplanen [The hidden

curriculum] (5th ed). Lund: Acupress.

Ziehe, T. (2008). ‘Normal learning problems’ in youth. Contemporary

theories of learning: Learning theorists... in their own words, 184.

Sunday, October 14, 2012

Teaching How to Choose

Making good choices seems to come naturally for some students while others need some coaching in order to become successful learners and be able to navigate with more ease within the educational systems. By allowing choices we also communicate our confidence in our students as learners – it is about letting them know we believe they can do it, without necessarily saying it aloud.

There are things in the classroom that must be done without getting into negotiations about how and why, and we truly cannot let students rule and do whatever they please in the classroom. However, allowing certain amount of choosing makes it emotionally easier for students to agree with the mandatory things. But this is not the only benefit of teaching how to choose. Only through our own choices we create accountability for our own learning and also train our executive functioning. Learning to make good choices is a skill to learn and it highly contributes to our higher level thinking. We should not deny that opportunity from our students by having too rigid rules that allow no choices.

How to add more choices into your classroom? During a regular day we have many opportunities to allow choices, starting from choosing whom to work with. By asking students to choose a partner who can help them in this assignment you are also encouraging students to recognize the good study habits of others. Giving younger students a package of content to be learned by the end of this week communicates your trust in their ability to choose the best pace for their own learning, and providing a timeline about how big fraction of the content should be finished by each day helps them understand the percentages, too. By letting students choose which assignment they want to start with helps them understand their personal preferences. Also, having a strong structure in the assignments allows the content to be more individualized. I think the ways of introducing more choices in learning environments are virtually infinite, if there is the will to make the change to happen.

My personal credo about best teacher being the one who makes herself unnecessary by empowering students become autonomous learners carries my values within it. I believe, that only by allowing students practice making good choices in an emotionally safe learning environment where their opinions or beliefs are never ridiculed, we can help the next generation reach their full potential and become critical thinkers. There is no shortcut to wisdom.

There are things in the classroom that must be done without getting into negotiations about how and why, and we truly cannot let students rule and do whatever they please in the classroom. However, allowing certain amount of choosing makes it emotionally easier for students to agree with the mandatory things. But this is not the only benefit of teaching how to choose. Only through our own choices we create accountability for our own learning and also train our executive functioning. Learning to make good choices is a skill to learn and it highly contributes to our higher level thinking. We should not deny that opportunity from our students by having too rigid rules that allow no choices.

How to add more choices into your classroom? During a regular day we have many opportunities to allow choices, starting from choosing whom to work with. By asking students to choose a partner who can help them in this assignment you are also encouraging students to recognize the good study habits of others. Giving younger students a package of content to be learned by the end of this week communicates your trust in their ability to choose the best pace for their own learning, and providing a timeline about how big fraction of the content should be finished by each day helps them understand the percentages, too. By letting students choose which assignment they want to start with helps them understand their personal preferences. Also, having a strong structure in the assignments allows the content to be more individualized. I think the ways of introducing more choices in learning environments are virtually infinite, if there is the will to make the change to happen.

My personal credo about best teacher being the one who makes herself unnecessary by empowering students become autonomous learners carries my values within it. I believe, that only by allowing students practice making good choices in an emotionally safe learning environment where their opinions or beliefs are never ridiculed, we can help the next generation reach their full potential and become critical thinkers. There is no shortcut to wisdom.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)